Posada Beyond La Catrina

A century since his death, José Guadalupe Posada left a wide heritage, not only engravings and skull, but he was a pioneer of editorial and graphic design in México.

Featured Contribution

- Comments:

- 0

- Votes:

- 1

- ES

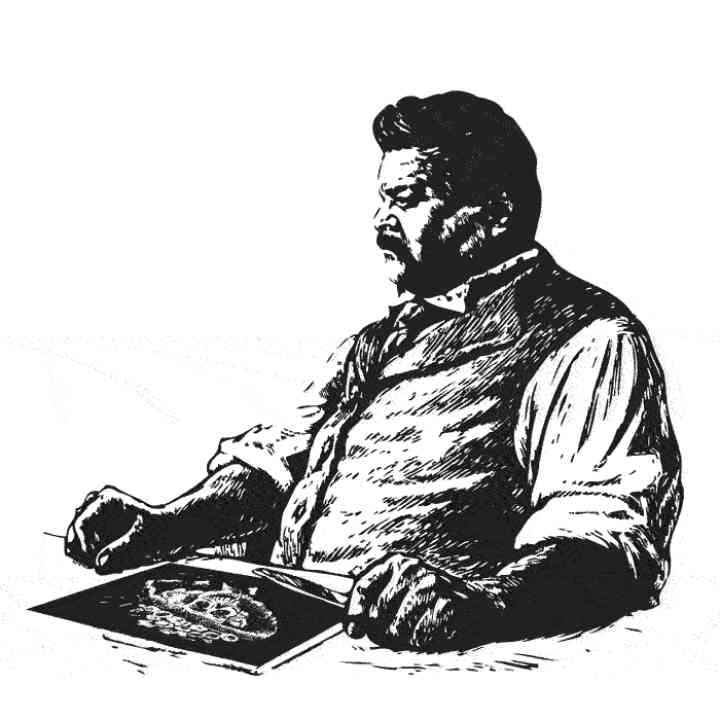

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar was born on February 2nd, 1852 at 10 pm, in former Los Ángeles Street

–which nowadays is called Posada Street– 47 and 49 in Aguascalientes City. He was Germán Posada Cerna and Petra Aguilar Portilloʼs sixth child, and he was raised within a countryside and poverty context among childhood games and working at the family businesses (bakery and pottery workshop). In the latter he would develop an interest for drawing and form. His brother Cirilo, 13 years older, who was teacher at an elementary school persuaded him to become literate and learn catechism.1 Cirilo took him to the Municipal Academy of Drawing. He was there for a short period of time, so it is not known how much he learnt there, maybe academic rules or copy prints to acquire drawing skills. Due to his familyʼs poverty situation, he was expecting to learn an office career to give them economic support. At 15, José Guadalupe Posada became painter.

We can state that Posada is the most important mexican engraver artist of all times. His prolific graphic art (twenty thousand prints) and his extraordinary quality allowed him to become the first universal Latinamerican artist.

At 16, in 1868, he started to work at José Trinidad Pedroza workshop, one of the best graphic artists of Mexico in those days. Posada became an illustrator there, performing lithography with excellency. At an early stage, Posada created his own artistic language and style, based on the reality. Not for copying it but to capture its essence and transform it into art. His language is strongly linked to popular culture and his work emerges from popular imagery. It represents hangings, crime, fusillades, monsters. All his concepts emerge from daily life, he retakes them and makes them appear bigger than real ones giving a high expressive content.

At 19, 1871, Posada created his first well known piece: a lithographic serie about eleven local state matters for the Jicote de Pedroza newspaper. The release of the images was an important event, and it made him «the best cartoonist of Aguascalientes». This early pieces showed a glimpse of a skilled drawer, lithographs were the only prints with an approach to local topics and characters.

On May 15, 1872, he and Trinidad Pedroza established a workshop in León, Guanajuato on Indio triste Street, that was sold later by Pedroza in 1876. Posada made commercial assignments to survive: calligraphy, saints prints designs, illustrations for books, cigars, matches, wine and liqueur packaging designs, birthday cards and commercial and social adds, for local and nearby customers. There, Posada consolidated their knowledge and career as illustrator.

On September 20th, 1875, he married María de Jesús Vela, a 16 year old girl, they had no kids. Posada had a kid, Juan Sabino, his only son who was born in 1883 and died at 16. It is unknown why Posada moved to Mexico City. It was probably because of the catastrophic flood of 1888 when some members of his family died, or the desire to try fortune.

His biggest influence were Romantic Mexican and foreign artists. Imported French book illustrations were printed at the workshop, these illustrations were inside romantic international trend that reached all intellectual fields of creativity.

Lots of newspapers asked Posada to collaborate and his successful work meant more work everyday. The mastering of his skills as engraver allowed him to reach a vital and direct language beyond triviality of topics and far from picturesque and vulgarity. He worked for several newspapers: El Jicote, El Teatro, La Gaceta Callejera, El Boletín, Gil Blas Cómico, El Popular, El Amigo del Pueblo, La Patria Ilustrada, el Diablito Rojo, La Patria Festiva, Revista de México, La Risa de El Popular, Entreacto, El Chisme, La Casera, El Diablazo, La Guacamaya, San Lunes, Aladino, El Padre Padilla, Almanaque de Doña Caralampia Mondongo, El Paladín, Almanaque del Padre Cobos, La Patria, Fray Gerundio and El Fandango among others.

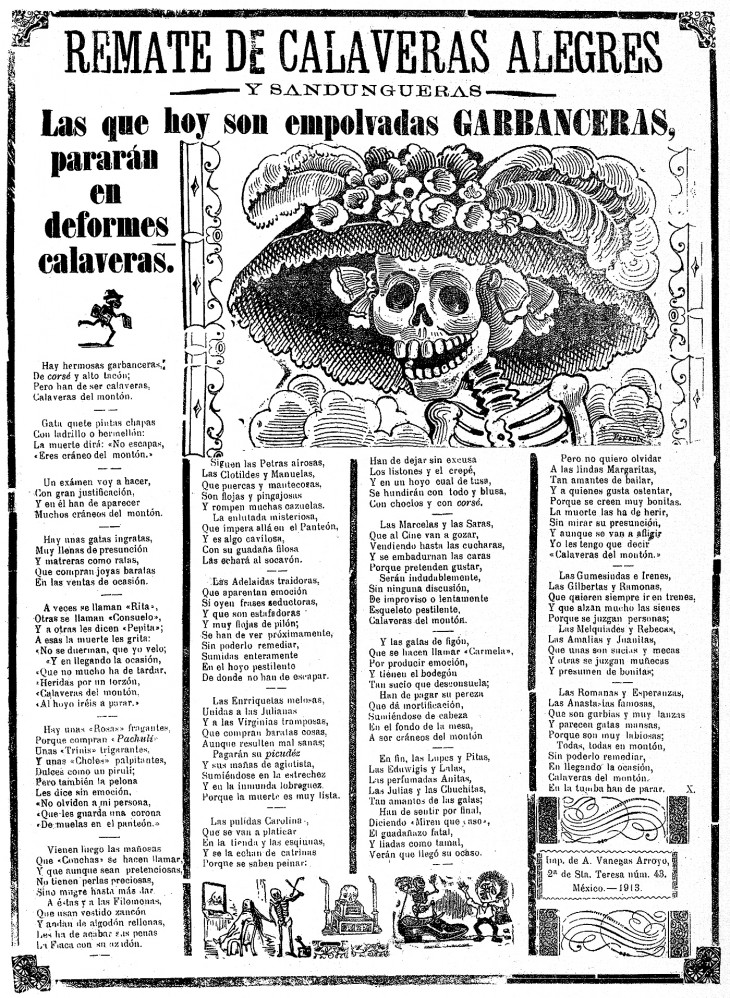

In Mexico City near 1889, publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo hired Posada; both had in common their audiences and the population, Posada worked for 22 years near 300 booklets there. In those days, a worker earned one peso everyday, so people couldn´t afford a book, but they could buy a cheaper booklet instead. The two supporters of editorial design then were Manual Manilla and Posada, text illustrated, songbooks, tales, riddles, epistolary, motto collections, kitchen handbooks, fancywork guides, syllabary, oracle, jugglery handbooks.

Studying the origins of Posada iconography we found knowledge and visual education based on observation of popular facts of the time and the high culture acquired by oral and written transmission of ideas and techniques or the daily interaction with skilled colleagues. The XIX Century is the golden age of popular art. With the death of absolutist ideas of divine power of government authorities, political, social and religion thoughts were born and this allowed expression and creation liberty. Artist represented no censored artistic concepts, breaking rigid traditions established by state and clergy despotism. Posada also worked on popular concepts of the age: songbooks and corridos (popular songs from the Revolution), as well as classic children´s tales.

A good engraving work, requires –needless to say–, a great deal of patience; and "Don Lupe", as he was called by his friends and coworkers, had that virtue to make his plates and give them the expression and the emotion needed.

He designed posters and play bills to promote public shows of the late XIX - early XX century Mexico. The playbills were hand delivered on the streets promoting bull fighting, circus, cinematographic projections, plays and cockfighting. Posada would work mainly for neighborhood stages, mostly for the Guillemo Prieto Theater. Playbills were usually printed on color China paper in small dimensions to avoid bothering the person on the next seat. The thinnest and smallest playbills were known as tiras (strips).2

Posada then moves on to formal, social and political experimentation of the calaveras; drawing Death makes it easier for everybody to make blunt critics and makes us all equal before death. Hence, the biggest heritage of Posada are skulls, final synthesis of our own heritage.

Who is La Catrina? This image has become a picaresque icon of death due to its flirty and joyful character. Created 101 years ago, during presidence of Porfirio Díaz, continues representing a mexican social class, and is also part of mexican culture. Quality of each of Don Lupe´s skulls, is remarkable, nevertheless, mexican people taste, choose one that had become national symbol: La Calavera Catrina. It was born called «Calavera garbancera», from "garbanceros"–rude, ordinary people– usually indigenous people who renegade from their culture and nationality, but at the same time, they use and imitate european habits. It has no wear, just a french style hat.

Using this image, Posada criticized those who pretend a lifestyle that do not belong to them; sarcastic, mocking and beautiful calaveras testify the life as something unworthy to take it seriously. Globally known, they are the most complete sample of his art and style.

An unusual feature of Posada images –unusual as well in popular art– are not masterly descriptions of poor people world, different popular characters or everyday life scenes. The extraordinary and where resides his historic sociocultural and artistic relevance is the fact that he represented that world with the same glimpse of the poor people: street people, pulquerías, or women in kitchen or market. In his engravings are expressed the thougths and pulse of mexican people.

As member of population as he was, he sought and expressed himself with solidarity. He was a tipical and totally mexican engraver whose characters were main characters, and he, with his art talked to people about their topics, struggles and needs, with their own imagery and feelings.

He made his work without a clear political ideology, but spontaneity and imagination, with empathy with his own people, whose he still evokes since his own thumb at Panteón de Dolores.

Posada left printed on several publications news, love, rage and sarcasm, the conciousness of his generation and a part of history of mexican art as one of the most important artist unintentionally.

Posada died on January, 20, 1913. His death certificate states that at 9 am José Guadalupe Posada have died because a acute enteritis and it was allowed to be buried freely at the sixth class of Dolores mausoleum.

Boost your career

Don’t just stop at reading. Discover our updating and specialization programs to take your professional profile to the next level.

View Academic OfferShare

Please value the editorial work by using these links instead of reproducing this content on another site.

- José Guadalupe Posada a 100 años de su partida. México, Índice Editores/ Iconos de Siempre. p. 22

- De los Reyes, Aurelio (2010) ¡Tercera llamada, tercera! Programa de espectáculos ilustrados por José Guadalupe Posada. México, Instituto Cultural de Aguascalientes. p. 13

Topics covered in this article

What do you think?

Your perspective is valuable. Share your opinion with the community in the discussion.

Comment now!